Siying Zhou is a research-based and project-driven visual artist working across multimedia and installation often exploring themes of culture, memory and ‘the Other’ within contemporary and historical Australian contexts. In this interview, Siying discusses art making as a way to communicate and participate within society; the impact of growing up in China in the 80s and 90s amidst the country’s shift from a socialist to a capitalist economy; and Siying generously shares about a plethora of art projects and collaborations from past years into the future.

Grab a cuppa tea (and put the kettle on for the next round) to enjoy reading about Siying Zhou’s creative journey.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your art practice.

I am a China-born artist who is currently based in Melbourne (Naarm). My other identities are: female in the age group 35-50; Scorpio in horoscope signs and Monkey in Chinese zodiacs. I also have few social titles: only child in my family, currently a Disability Support Worker, and a member of the editorial advisory committee of Un

Projects. In my late 20s and early 30s, I worked as the gallery manager of 24HR Art (currently Northern Centre for Contemporary Art) in Darwin, a lecturer of interactive scripts, and an independent curator. When I reached my late 30s, I began to prioritise my art practice and establish my artist career.

My practice is mostly identified within the visual art discipline. I work with multiple media, such as photography, video, ready-made products, found objects, textile, food and performance, and predominantly produce installation works. In my installation works, fragmentation, contradiction, slippages and humour are used to create a hybrid, parafictional and contemplation space for audiences to engage. My art practice is drawn upon self-reflection on my Chinese heritage and my ongoing interrogation of the ontological value of the female Asian immigrant to western societies. The ideas about being Other is consistently explored in my works. I use my art practice as a research method to participate in sociological and philosophical discourses about culture, history and memory. Through my art practice, I search for my position in not only contemporary Australian society, but also in the history of Australia. As I often include participative projects in the research process, I perceive my practice as a means to generate communities.

I have received a Bachelor of Visual Art in Nanjing Art institute, China in 2002, and Master of Multimedia Design in Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney in 2005. Recently, I obtained a Master of Contemporary Art and Master of Fine Art from Victorian College of the Arts, the University of Melbourne in 2015 and 2018.

How did you start your creative practice and why?

I decided to have a creative practice at a very young age. I was a lonely child. I never have a strong desire to speak. I was attracted more to visual stimulation than words. So, making images become the natural means for me to explore the world and communicate with others. When I was 12 years old, I was accepted to a school that was specialised in training western art drawing and painting. But my creative practice wasn’t really formalised until I went to Nanjing Art institute where I studied and completed a Bachelor degree of visual art. I came to Australia to study contemporary art. Although I have made all my life decisions to have and keep an active art practice, my practice is not always continuous. In fact, I felt ambivalent to call myself an artist and establish an artist career until I studied my 2nd Master degree course in fine art in 2015. (I would like to address that ‘artist’ and ‘artist career’ as we commonly understand it, are western terms. They reference western cultural tradition and evoke capitalist economy mentality.) I only slowly grasp what it means to be an artist and have an artist career from working in Australia’s contemporary art industry. But I guess people can have a creative practice without having an artist career.

The reason to have a creative practice was very simple at the start. I followed my instincts and things I am attracted to. But when I grow older, the reason becomes more complex and tactic. The older I become, the less choice I have. I gradually realise that it is only through art making that I can see the meaning of life, that I can fulfil my value as a human to societies, and that I can get in touch with others.

Where did you grow up and has it influenced what you create?

I grew up in China and spent most of my childhood in Nanjing. But I also lived in Shanghai from age 5 to 9. It was the 80s and the 90s. China back then was a very different country from today’s China. China was on the cusp of several social and economic transitions. It just began to shift from a socialist to a capitalist economy, from an unrecognised nation cut out from the west to a country with a wide international trade connection. My childhood was in the thick of these dramatic national changes and caught the end of Chinese ‘pure’ socialist life. The lived experience of the socialist society has laid the foundation for my moral values and my perception of the world. The idea of equal wealth and the community prioritised thinking patterns that continue perking back of my head and shape my perception of today’s world.

Growing up from China at that time has passed on historical social trauma to me from the previous generation. The stories about the atrocities of the Cultural Revolution in the 70s and Nanjing massacre during WWII were not only educated at schools, but also passed down by family and heard through gossip in friend circles. At a young age, I was implanted with a sense of loss and an untrusting attitude towards human society. And, the sense of loss became personalised and intensified when I grew older. Under the central government’s vision to build ‘modern’ cities and ‘modern’ life, Nanjing city had gone through a huge gentrification. Many old streets and buildings did not survive. The places holding people’s memories were wiped out so quickly that people didn’t have a chance to process the imposed change. People were herded to move ‘forward’ and rest their gaze at ‘future’ and the ‘past’.

In the 80s and the 90s, the practice of Russian realistic oil paintings and sculptures and Chinese traditional art and craft were all very strong and present. Although I was trained in western drawing and painting, I was exposed to various aesthetics of Chinese art and learnt about philosophies projected in ancient Chinese art and the history of Chinese art. The visual memory and knowledge of the non-western art have definitely influenced my art making in current time in Australia.

Arts & culture in Nanjing is strong. With several major universities, Nanjing attracts many artists from surrounding cities and towns to reside. Hence, it always has a large artist community. However, the artist scene in Nanjing is quite different to ones in other major cities, such as Shanghai and Beijing. It projects a docile and romantic attitude of artists. The artists in Nanjing tend to not seek the international recognition and validation, but rather, are satisfied with the focus on the domestic audience and the artistic discourses that relate to events and fairs in their everyday life or refer to Chinese history. Growing up and learning art in an atmosphere like this, I think I more or less inherited such an attitude to respond to art politics. Overall, my upbringing in the 80s and 90s’ China and Nanjing has definitely drawn an important parameter for me to refer to when I examine my artist role and immigrant role in my contemporary Australia life.

Tell us about your past creative projects. What has been a career highlight?

I always feel it is difficult to choose and pick between my projects and define highlights. Every art exhibition and project I have worked on and completed is a milestone for me because no single art exhibition and installation comes out from an easy process. But of course, talking about every exhibition and work I have made so far requires a large space on pages. So, I let my memory choose and find a few to share.

Art on wheels, a community art project in 2011 in Darwin

When I worked as an independent curator in Darwin, I produced and curated a project called Art on Wheels under the auspice of Darwin Visual Art Association, the only artist run initiative organisation in 2011. With the luck of receiving the grant from Australian Council of the Arts, this project turned a 1989 Toyota van into an art gallery space and carried artworks and art activities created by 15 Darwin and Melbourne visual, sound and performance artists into various suburbs and public locations in Darwin for a month. Even though the shortage of human and material resources in Darwin at that time made the production and implementation of this project challenging and tough, I had many great memories of working with extremely supportive artists, art workers, and people outside the art community.

During this project, the van went to many locations that were considered as conventionally non-art spaces: the only shopping mall in Darwin, a library, all the markets, and suburbs. It was great educational and rewarding to witness how the public responded to the unexpected art content in their daily activities and expressed appreciation toward such experiences. Looking back now, I think perhaps only Darwin could pull off the project like this.

NotFair 2014

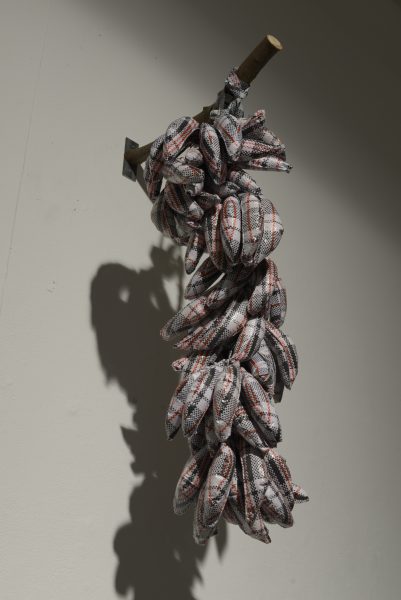

It is one of major commercial art events in Melbourne. I had two works shown in 2014. The works were the outcome of my early artistic exploration and examination about the relationship between Asian immigrants and Australian land. One of the works, titled The Comforting Promises, was a soft sculpture made of the material of the blue and red travel bags and shaped in a bunch of bananas was sold on this occasion. This work was informed by a story that I came across. The story said that the earliest appearance of bananas was spotted in the Chinese camp in the early gold rush period. Regardless, much truth was in this story, it gave me a fictional space to connect the identity of Asian immigrants and the Australian imported food. It was also a reminder that ‘banana’ was used as a euphemism for East Asian people who were born and grew up in the Western world. On one side, this work reflected my commentary on the contemporary Australia that was lived on a land colonised by the food plantation and farming fields of foreign spices; on the other hand, it marked my attempt to understand the contradiction embodied in the immigrants’ mindset: an unerasable attachment to their past and a desire to break from the past.

This work was sold at this event and it was my first art sale.

Feeling Invisible at the dinner without lamb, 2015.

This was an artwork developed and produced in collaboration with Steven Rhall, Taungurong artist, in response to the call-for-works at the exhibition titled Both Sides of the Street, curated by Blak Dot Gallery, Counihan Gallery. By making this work, we pondered the relationship between the contemporary urban dwellers in Melbourne/Naarm and land and exchanged our different personal connections to this land. It was a great fun collaboration process, from conceiving the project idea at a Greek restaurant on Lonsdale street to making concrete castings of rabbit burrows in an open field in Maribyrnong. Before we poured the concrete in the burrows, we performed different rituals, based on my Chinese cultural experience and Steven’s knowledge about his Australian indigenous culture. The rituals were to give thanks to animal and land spirits and express our apology for the disturbance. In Counihan Gallery space, we hung the concrete castings from the ceilings and projected the video image of the traffic on West Gate Bridge.

My food project from 2013- present

Since 2013, I have been using food making and the activity of food consuming as a strategy to explore cultural matters and the ideas about self and other. It started from the actions that I dissected symbolic Australian food, such as meat pies and ham, cheese sandwich, and replated them to the table wear that had Oriental decoration features. The food in the end was presented like a meal on an Asian cultural dining table. The video work that recorded the actions was titled Pie to Pai. Through these food ‘translation’ actions, I challenged the definition of a particular culture and expectations stimulated by the cultural names, such as Australian food, Chinese food, or Japanese food, etc..

2013, Siying Zhou.

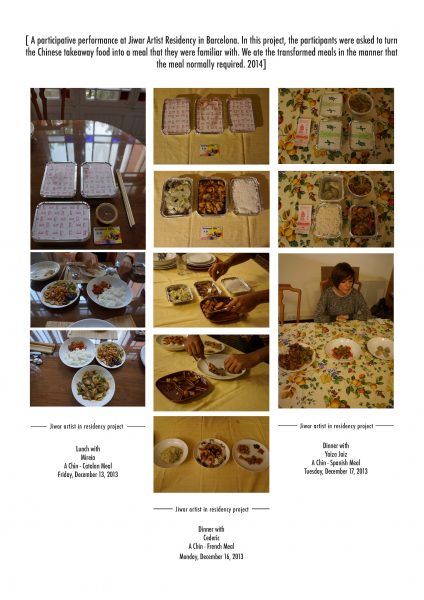

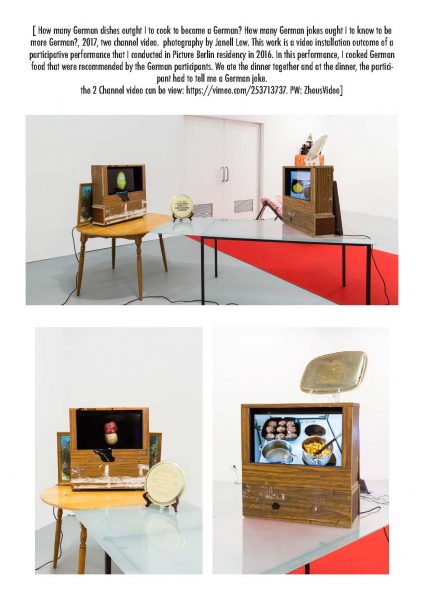

Then, I realised that food making and sharing were a great means to quickly establish social networks and assemble a community. It was also a good way to generate research materials and artistic subjects. In both my residency at Jiwar, Barcelona, 2013 and at Picture Berlin, Berlin 2016, I used food to generate projects, build social connections and research about cultural subjects. In the Barcelona residency, I asked the local participants to turn the Chinese take-away dishes I purchased from local Chinese restaurants into dishes that they felt familiar with in their own cultures. They dictated how these dishes were served based on table etiquette in their cultures. We made conversation during the meal. In Berlin, I asked German participants to send me a German food recipe. I cooked the German dish based on the received recipe and invited the participants to dine with me. At the meal, they were asked to tell me a joke.

In 2020, when the lockdown was first introduced to Melbourne due to COVID pandemic, I suddenly had to accustom myself to the isolated and lonely life in my apartment. In the isolation, my gaze was turned to myself. My mind was often stuck in the memories of the past. Meanwhile the fear of touching people due to transmission of the fatal virus, had made me contemplate about the connection and distance between people. I raised a propositional question: Can a person’s memory be infiltrated from internalising others’ memory? Would food consuming provide a means for an individual to embody other’s memory? If one inherits others’ memory, does it mean the personal identity could become a fluent and changeable subject, and the distance between people could be reduced?

I explored the answers to these questions through a participative project titled Taste Your Memory. In this project, I invite the participants to exchange the recipe of their favourite childhood dish with me. By following the cooking and eating the dish from the given recipe, we connect online and share our memories about the dish in exchange and the process of cooking in the present time. I had a total of 15 participants in this project and received a rich amount of narratives and materials to work with. I am still working on this project and trying to develop these collected materials into a body of artworks.

MFA project 2016- 2018 & Winning of Linden Art Prize

From 2016 to 2018, I undertook study in Master of Fine Art in Victorian College of the arts and implemented a two year long practice-lead research project titled It’s neither this nor that. In this project, I seek for material and spatial representation of the ‘in-between’ cultural position. This project is concluded with an installation and a reflective paper. The installation consists of several multimedia works that I created during the research, including The National Anthem of AO-SSU-CH’IU-LEE-A. A Karaoke video; Just call me JO (sculpture); A cooking lesson of making steam hot crossbuns. (two channel video); Large candle coils (sculpture and videos); How many German dishes ought I to cook to become a German? How many German jokes ought I to know to be more German? (two channel video); Takeaway-Stayaway (LED light); Stubby covers for Chinese crockery (Sculpture).

This research, drawn from my own experiences as both an immigrant and a tourist, investigates the cultural space of ‘in-between’. I explore the possibility of demarcating this in-between position by working with culturally disparate objects and images to create temporary material artefacts. By constructing an installation, I ask if the unhinged and dislocated cultural experience of the in-between can be transposed to other people.

Using everyday objects, images, languages and commonly practiced activities, I locate four intercultural events, and their related scenarios, in the form of sculpture, videos and performance. Each scenario depicts a propositional mode of cross cultural interaction. Through this creative process, the ideas of the in-between transpire from the dynamic articulation and representation of culture difference. In this research, language, human body, material form and geographic sites are perceived as various forms of cultural representation, manipulated to construct cultural conflicts and negotiation. Incidents, such as, phonetic translation, transformation of one’s cultural identity, the appropriation of the existing products and the human intervention of a geographic site, present as the interruption in the signification process of the existing cultural forms. These reveal the openings in the linguistic structure, the idea of the Self, material composition and the cultural identity of a place. Through these openings, the in-between is represented with the notion of cultural hybridity as a unique place of forming culture and the Self.

Two works developed from this research project won me the Linden Art Prize in 2019.

Ararat Residency 2019

In November 2019, I was invited by Ararat Art Gallery TAMA to undertake an artist residency in Ararat to engage in the local history of the Chinese community. I spent a month living in Ararat making personal connections to this place. As a result, I encountered a unique contemporary revelation and representation of the disappeared past of Ararat. In contrast to the untraceable human history before the colonial farming, the historical short existence of the Chinese in Ararat is educated in Gum San Chinese Cultural Heritage Centre and addressed by a passionate community group, called the friends of Gum San, although it also has little visibility in the current townscape. By speaking with the local community members and visiting the sites where the brutal events took place that caused the inoccupation of the Djab Wurrung in Ararat, I had experienced an unfamiliar and discontinuous past that is informed by her present contact. In response to the experience of this residency, I created an installation and exhibition titled Drawing dashes between dots. In this work, I examined representation of history and different contemporary relationships to the past. By presenting multiple narratives in different perspectives, I intended to map out the entanglement between the idea of personal identity and history.

Besides these art projects above, my career highlights also are marked by the group and solo exhibitions I have participated and held nationally and internationally. They include: The hearts of the people are bigger than the size of the land, produced by and curated by Olivia , in Rising festival 2020; Momentum, West Projections Festival, VIC. 2020; We Are We Eat, A touring exhibition curated by Sarah Perrie and shown at Godinymayin Yijard Rivers Arts and Culture Centre, Katherine; Araluren Arts Centre, Alice Springs; Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, Darwin, NT 2019-2020; Nessun Posto, Trocadero Art Space, Melbourne; National Anthem, Buxton Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2019; Those Monuments Don’t Know Us. Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, Melbourne 2019; Rifts: particular matter, Testing Ground, Melbourne; Video Visions 2017, Channels Festival 2017, ACMI, Melbourne; Ohrwurm, Meinblau Projektraum, Berlin, 2017. Solo exhibitions: George Prefers Fork, Blindside, Melbourne, 2020; Drawing Dashes between Dots, Ararat Art Gallery TAMA, Ararat, 2020; We Watch Them To Be Ready For Their Arrival, C3 Contemporary Art Space, Melbourne, 2019; Disguise Me. 明月松间照,清泉石上流, Mailbox Art Space, Melbourne, 2019.

I have also received awards and grants, such as Linden Art Prize 2019; Community Grants, 2018/19 Small Project Grants, The City of Yarra; NGV Women’s Association Award 2017 and 2015; John and Mary Kerley International Travel Scholarship, 2016; Queensland Centre for Photography Best Use of Natural Light, CCP Salon 2015; The winner of The Balance exhibition, Northern Centre for Contemporary Art 2013 Members Exhibition

What do you hope audiences take away from your work?

I hope my works would offer audiences both a stimulating multi-sensory viewing experience, but also a space for thoughts. I would like audiences actively to engage with my work. By visiting my works that often appear to be obscure, fragmented, and conflictive, audiences would use their imagination and knowledge to make connections, logic and meanings about the works. In this way, what they take away is not fully from me, but also created by themselves. I also would like to use my works to poke people’s comforts and formality. I hope audiences would feel entertained as well as troubled. Ultimately, I hope that my work can provoke new ideas, new knowledge, new perspectives and new questions for audiences. I hope that there are some parts in the works that might not be comprehended at the moment of viewing, but would stay in the audience’s memory. One day in the future, they will reveal its meaning to the audience.

Who or what inspires your art?

Many things have inspired my art. They are from artworks and artists to certain moments I encountered in everyday life, or the stories and jokes I heard and read or protagonists in movies. I have a list of international and Australian artists whose art practice I admire and often look up. If I must name one here, I’d like to share my affection towards David Hammons. I read about David Hammons’ art practice and works from the book David hammons Bliz-aard ball Sale by Elena Filipovic. I feel David and I share many things as artists, particularly, a quality of staying invisible and on the edge of the centre of the art world. But I think that David’s invisible state was more active and intentional than mine. I admire how David presented his black-American identity to the contemporary art industry through an implicit approach, even though he knew that directly quoting his black identity in his works would gain him an easy success in the art industry. He insisted to use his own presence to narrate his racial identity, and evoke everything attached with this identity. In his performative works, the racial narratives were rarely specifically address, but very much in the presence. I really wish I had his courage and confidence to enjoy a creative freedom, stay ‘unknown’ and resist to the trend in the mainstream art. With all his ‘un-documented’ ephemeral works, he was like a ghost that actively

responded, criticised and influence politics of the art. He became a myth

and a legend that only existed in passing people’s memories and

passed on through words of mouth.

Where do you feel most creative?

Library, my studio and excellent art exhibitions. I know when I say library, it would make me sound uncool. But when I am immersed in books and read them, my mind becomes so active and is often exploded with imagination and many ideas. I also love working at my studio and translating thoughts and ideas in my head into images and objects. In the process of making, unexpected things appear for me to learn and manage. It pushes new ideas and visions about what I am making. I am also often inspired by visiting art galleries and museums.

What gets you through challenging creative/ industry times?

It depends on what kind of challenges and difficulties. But I guess whatever the challenges that I encounter in creative production, would more or less impact my psychological and emotional states. Through years of practice, I have learnt a few small ways to help myself come over emotional down-time. I find that taking a break from the art every now and again is helpful. It allows me to readjust my thoughts and gain fresh eyes to return to the art. I deliberately choose a paid job that is not related to the art industry. It gives me a natural cause to take my mind off the art. Before the pandemic, I would also go to art galleries and museums, cinema, library, or bookstore to take the troubled mind off. However, the last two years of the COVID lockdown life had made these self-manageable methods very difficult to apply, as many public places were not accessible. The challenges brought by the COVID lockdown restrictions were extremely psychological. I found myself turning to my close friends for help. Having a chat via message or zoom with them often calmed me down and gave me motivation.

What future projects/creativity are you looking forward to?

I have three upcoming exhibitions and projects that I am currently working on and excitingly yet anxiously anticipate to see their outcome. One of them is a body of works that I have been developing collaboratively with Ash Perry, a Goenpul artist from Quandamooka country in the last two pandemic years. The works will be shown at the Substation for Hyphenated Biennial from December 3 – April 9, 2022. It has been an incredibly tough and challenging journey doing a collaborative project during the pandemic and through lockdowns. I am quite proud of what we have achieved so far and hopefully the final installation of the works will be satisfying.

Our collaboration initially was to explore how the games we played in our different childhoods inform our critical views towards the capital economic system. Due to the COVID lockdowns, our collaboration moved from the studio space to the online conversational space of zoom. From the conversations, we slightly shifted the focus from our personal past to the present and realised that not only our past informed the present us, but our present selves gave us a perspective to look back at the past. We decided the best way to engage with the past was to dwell in the present and gain an understanding about living as artists in the current social, political and economic climate. We shared how our identities as a Chinese immigrant and a First Nation person shaped by the past have shaped our experiences of working as artists and building artist careers in today’s Australian art industry. We explored various elements under the visible surface and beyond statistics that shape an individual artist career and lead to success in the art. We also examined the different social aspects that shape evaluation systems in the art that are not only by individual subjective views and tastes.

Three works have been developed from our conversation and artistic research for Hyphenated Biennial. They are The Fine Print, a text work displayed on a lightbox; Scratch Card.Sick Art Prize, a participative work inviting audience to play the game of scratch cards and win Sick Art Prizes; Weight of High Spirit, a balloon installation consisting of 200 metallic balloons in trophy and star shapes inflated by failing and covid-free artists’ breath. We hope these works will be received well.

I am also currently working with Tammy Hulbert, curator, Ai Yamamoto, a sound artist, Rosemary Joy, Arts Activation Program Lead in Maroondah City Council, and four Chinese residents in Maroondah area to explore historical and contemporary Chinese-Australian connections to the local area. This project will produce a multimedia exhibition at Artspace, Realm and will open to the public from February 2022.

Finally, I will hold a solo exhibition at FELTspace, Adelaide in February 2022, showing the 6 Channel video work that I created in response to my artist residency at Ararat in 2019. The title of the show is Calling the Dead. If anyone from Melbourne will travel to Adelaide by then, please check it out.

All these projects and exhibitions mentioned above are the works carried out from the past to near future. In the distant future, I would like to locate funding and work on a project to explore the relationship between racial representation and arts. I plan to work with members of Melbourne Peking Opera Club and develop a Peking Opera performance with them. Established in 1988, MCPOC is a community group populated by mainly Chinese immigrants from the mainland. Most of the current participants are seniors, including professionally-trained Peking opera musicians and singers, as well as hobby-practitioners. The club holds regular performance and rehearsal gatherings in Box Hill, Melbourne, the suburb known as a Chinatown outside the CBD. Meanwhile, I will try to discover more materials about the Oriental Concerts that the Chinn family performed in Victoria in 1931 and 1933. I came across the narratives about the Chinn family’s musical performance in previous research in Australian Chinese history. An Australian-born Chinese family, Mrs. T. C. Chinn and her children, received a Western musical education and gave many public performances in Victoria during the 1930s and 1940s, including The Oriental Concerts. Their performance was famous for its Western pop-classical style, decorated with the elements of Chinese culture. I would like to produce multi-channel video and sound works, as well as images, text, and sculptures to conflate the narratives about the Chinn family with a presentation of Melbourne Chinese Peking Opera Club. By interspersing the narratives of two musical performances and Chinese female musicians from different times, this project examines the problematic link between the racial representation and the arts. It proposes alternative narratives about Australian cultural identity and history that are informed by the narratives about Eastern Asian diasporic and immigrant women, visualized through their performing and labouring body, and shaped by their gender perspectives.

This project idea was formed early this year. Sadly, I haven’t got much luck in finding funding to support the development of this project and artistic exploration. So, hopefully, sometime in the future, this project can be realised.

Where can we find and follow you online?

My website: siyingzhou.com

My Instagram: @siying_z

Featured image: Siying Zhou. Photo credit: Leah Jing McIntosh. All images courtesy of the artist.