Abdul-Rahman Abdullah is a seventh-generation Australian Muslim whose artistic practice primarily focuses on sculpture and installation. His practice explores the intersections of identity, culture and nature, experimenting with surrealist elements. Abdul-Rahman has exhibited in over 90 projects throughout his career including festivals, biennales, art fairs and solo shows. He recently collaborated with his brother, Abdul Abdullah, and Tracey Moffatt on ‘Lands Abounds’ at Ngununggula Gallery investigating our relationship to land, wealth, ownership, power and privilege.

In this Colour Box Studio interview, Abdul-Rahman shares details about his upcoming work for the Tarrawarra Biennial in Healesville which reflects on the ideas of cultural geography and the inherent violence of territorial behaviour. He also discusses the isolating and universal, yet sanitised, nature of death and how his work Pretty Beach explores these themes while honouring his late grandfather.

How did you start your creative practice and why?

I always intended on becoming an artist from when I was a kid, although it took me a long time to know what that might look like. I became an artist after graduating from Curtin University in 2012 at the age of 34 and have never looked back. Prior to that I had a variety of crappy jobs, as well as working as an illustrator, designer and model maker, weirdly specialising in Zoo and Christmas display. I had a long, windy road leading to the work I make today.

80x110x230cm, painted wood

Murdoch University Collection

Photograph by the artist

Where did you grow up and how has it influenced your practice?

I grew up in Victoria Park, an inner city area of Perth that used to be quite dodgy in the eighties and early nineties, full of cheapo caryards, laneways, hock shops and op shops. It’s much fancier now but still one of the more interesting parts of the city.

I live on a cattle farm now, surrounded by animals and nature. I grew up in a super haunted house built in 1924, moving out when I was eighteen. Everything about my childhood still informs my creative practice today. I think that it’s so important to recognise that you’ll always be the child you were, we just accrete layers of experience, information and relationships. That inner dialogue doesn’t respect the passage of time, it just meanders on berating, singing, yelling and whispering contradictions until we die. Listen to that voice and you’ll find all the ideas you’ll ever need.

250x550x550cm, painted wood, chandeliers

Private Collection

Photograph by the artist

Tell us about your past creative projects. What has been your most treasured creation so far?

I’ve had so much fun over the past decade of being an artist, participating in around ninety projects, including festivals, biennales, art fairs, curated exhibitions in small, medium and large spaces, as well as seven solo shows. I think I’ve produced about 120 works over that time. I think my favourite outcome was creating a large work titled Pretty Beach for The National at the Museum of Contemporary Art in 2019. The work offered a way of processing and honouring the suicide of my Grandfather ten years earlier. Art has the capacity to embody universal ideas from profoundly personal experiences.

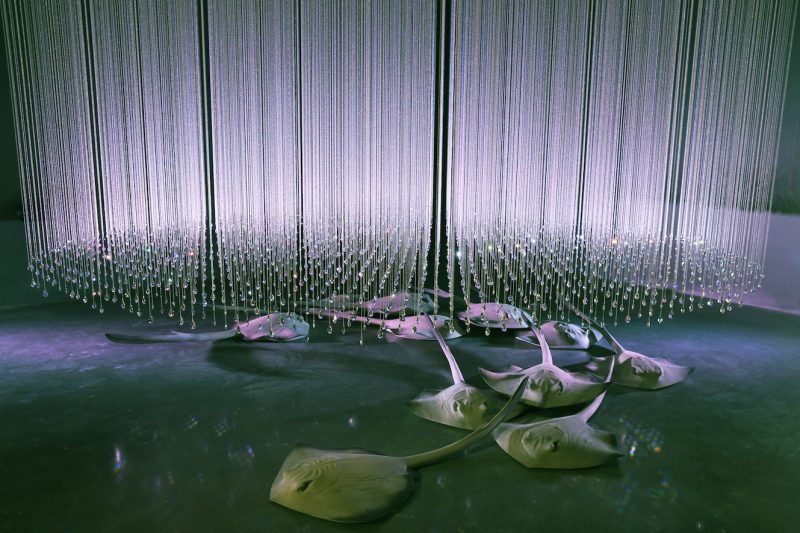

500x490x490cm, painted wood, audio, silver plated ball chain, Swarovski crystals

Private Collection

Photograph by the artist

Tell us about your current project.

I’m currently finishing off a large work for the 2023 Tarrawarra Biennial in Healesville, regional Victoria. The Biennial, titled Ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili is curated by Léuli Eshrāghi, a beautiful human who embodies cultural paradigms paralleling my own in rich and unexpected ways. I’m creating a work called Tanpa Sempadan, meaning ‘without borders’ in Malay, it’s a 4.5m albino saltwater crocodile carved in wood, reflecting ideas of cultural geography and the inherent violence of territorial behaviour.

60x216x290cm, Stained wood

Photograph by Zan Wimberley

Who or what inspires your practice?

I’m inspired by my children, the environment that I live and work in and my favourite artists – my wife Anna Louise Richardson and my brother Abdul Abdullah.

Where do you feel most creative and why?

I feel most creative when I’m in my studio. It’s my world, my party and my fortress. I love it.

What do you hope audiences take from your work? What feedback have you received from a show or work?

The best compliments that I’ve received from my work has been the ongoing responses to Pretty Beach (2019). Every time it has been shown, audiences have responded with their own experiences of grief and loss. There have been many tears and vulnerable moments with complete strangers. It’s incredibly beautiful to make a work that allows people to open up about some of their most fundamental experiences that have been sanitised from our public interactions. Death frames our lives in so many ways, yet so often the experience of it can be isolating and frustrating. This work wasn’t a solution, it was a way of communicating something universal.

180x170x190cm, painted wood

Art Gallery of Western Australia Collection

Photograph by Kai Wasikowski

What future projects are you looking forward to?

All of them!

Whose work are you digging at the moment?

Right now I’ve been fanboying the work of my friend Shireen Taweel. Her intricate, hand cut copper sculpture describes something so familiar within me, like a kind of spiritual architecture that exists only in my memories. Look her up, she’s amazing.